“The problem is that white people see racism as conscious hate, when racism is bigger than that. Racism is a complex system of social and political levers and pulleys set up generations ago to continue working on the behalf of whites at other people’s expense, whether whites know/like it or not. Racism is an insidious cultural disease. It is so insidious that it doesn’t care if you are a white person who likes black people; it’s still going to find a way to infect how you deal with people who don’t look like you. Yes, racism looks like hate, but hate is just one manifestation. Privilege is another. Access is another. Ignorance is another. Apathy is another. And so on. So while I agree with people who say no one is born racist, it remains a powerful system that we’re immediately born into. It’s like being born into air: you take it in as soon as you breathe. It’s not a cold that you can get over. There is no anti-racist certification class. It’s a set of socioeconomic traps and cultural values that are fired up every time we interact with the world. It is a thing you have to keep scooping out of the boat of your life to keep from drowning in it. I know it’s hard work, but it’s the price you pay for owning everything.”

– Scott Woods

This quote has spent the past several days circulating among my Facebook friends, and it in combination with some internet infighting has made me really want to address the understanding and use of “-isms.” Racism, Sexism, Cissexism, are all examples.

(It’s somewhat unfortunate that the above quote regards racism, because that is the one “-ism” that doesn’t follow the sort of language pattern I want to discuss. But, the description of the term as it is can be applied to most any “-ism.”)

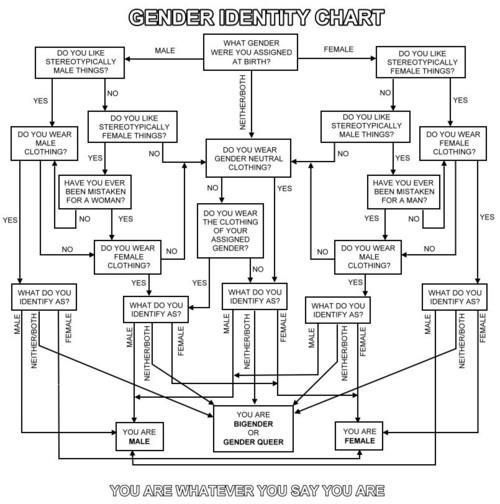

There is an important actual and linguistic difference between individualized and institutionalized marginalization. Individual marginalization has terms like misogyny, transphobia, homophobia, etc. It refers to the ways in which a person or discrete small group of individuals are hateful to another. The “-isms” refer to institutionalized, internalized, ways of thinking and behaving that marginalize others without any conscious intent to do so. Here are some examples:

If a man tells a woman he’s going to rape her because she refused to accept his romantic advances, he’s a misogynist. If a person with no ill will toward women honestly believes women are “just different” and that’s why women are often less successful in science and math, they are being sexist.

If someone calls a trans* person a “trap,” or a “tranny,” they’re being transphobic. The fact that people actually feel the need to legislate the use of “correct” bathrooms because they’re really concerned about how genitalia align with bodily functions, they’re being cissexist. Or, for a more “polite” example, when every fucking interview with a trans* person crashes and burns because the interviewer asks about the interviewee’s genitalia, those interviewers are being cissexist.

Waving a sign that says “God Hates Fags” is homophobic. When a gay couple gets married and everyone legitimately wonders who’s going to wear the dress vs the tux (no matter the gender of the couple), that is heterosexist, though in this case the term more frequently used is heteronormative.

Telling a polyamorous person that she is “cheating” on her husband with her other partner(s) is polyphobic (I’m not 100% sure that’s a word, but it really ought to be). When filling out a medical form regarding sexual history, and there’s only one space for a “primary” or “main” partner, that’s monogamism.

And, as I mentioned at the beginning, racism is more difficult to parse out because there is only one term. If someone calls a black person the n-slur, they’re being racist.The appropriation of the cultural mores of another race because you think it’s fun and will make you cool, is racist. The prosecution of drug charges that results in an overwhelmingly black prison population, is also racist. The differences in behaviors and intentions all just have one word, and frankly throw my whole argument out of whack. But, it wouldn’t be the English language if a few words didn’t follow the rules.

The upshot of all this, as with any of my commentary about marginalized groups, is to check your privilege before you say something. No, you might not be transphobic, you might not be homophobic, you might not be polyphobic or misogynist or a hateful person of any sort. But, the insidious thing about “-isms” is that they can thrive without hate. They can be perpetuated without malice or intention. As Woods states, “It is so insidious that it doesn’t care if you are a white person who likes black people; it’s still going to find a way to infect how you deal with people who don’t look like you.” Whether or not we “like” black people, gay people, women, etc., we still view those who are different from ourselves in particular ways that can very easily become marginalizing.

If you are not a member of the particular marginalized group you’re discussing or interacting with, you’re liable to fall into an “-ism” trap because that’s just the way we’re brought up to think. Woods refers to this trap as a vast ocean we’re floating in, “a thing you have to keep scooping out of the boat of your life to keep from drowning in it.” The privileged perspective that gives rise to the many “-isms” is an integrated parts of our lives that we have to consciously and constantly resist in order to truly support those who are not privileged in the same ways we are.

This last bit about “in the same ways we are” is important. A lot of people think they can’t be marginalizing because they are marginalized. Being poly does not make you magically a queer ally, being trans* does not make you immune from racism, etc. Every group carries unique sets of privileges that allow them to marginalize other groups.

There are already a lot of resources addressing how to deal with privilege and be a true ally, and I don’t think I need to become one more. The simple point I’m trying to make is that a lot of us think that just because we aren’t hateful people means that we automatically do not marginalize others, and that’s simply untrue. Not being hateful is a solid baseline, but to work our way out of the deeply ingrained “-isms” that teach us what is normal and what is other, is an ongoing and difficult process. Though, I would argue, it is a necessary one to be an actualized person and full member of humanity at large.

There is a new comedy playing on NBC entitled

There is a new comedy playing on NBC entitled